Star Forming Galaxies and Host Dark Matter Halos

Research | | Links: [OIII] and [OII] Clustering paper | Lyα Clustering Paper

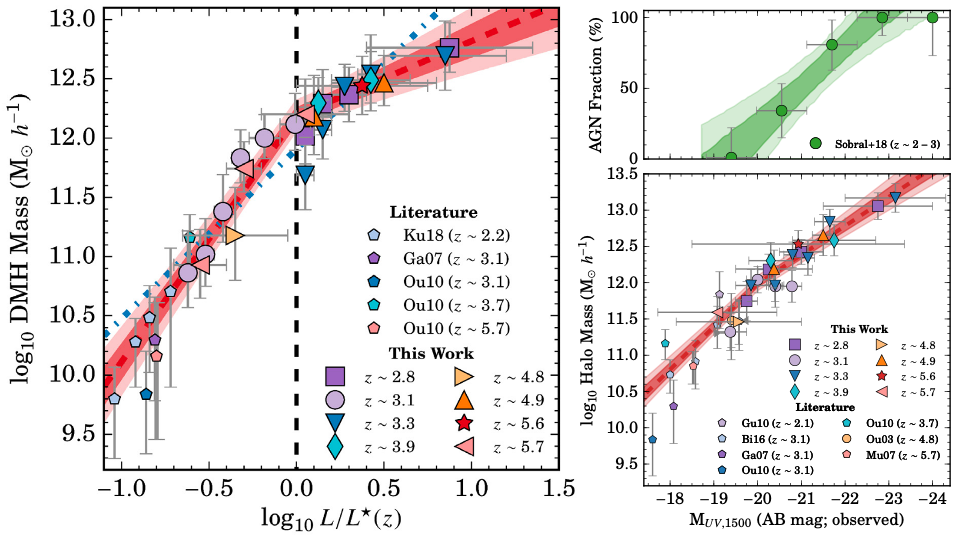

Host Dark Matter Halo Mass and its correlation with Lyα and rest-frame 1500Å luminosity Khostovan 2019. These two plots highlight two important key features: 1) correlations are redshift independent when taking into account evolution in line luminosity, 2) bright (high SFR) galaxies tend to reside in higher mass halos, and 3) there is evidence for a transitional halo mass at L > L* where star-forming galaxies become rarer within increasing luminosity. This is also seen for bright UV Lyα emitters which are > 50% likely to be AGN at \(M_{UV} < -21\) mag.

Spherical overdense regions known as dark matter halos (DMHs) massive enough (have deep gravitational potentials) to facilitate cold gas accretion are the sites where galaxies form and evolve. The stream of cold gas falling in within a galaxy is the material that fills the reservoirs of gas inside galaxies which is then used in star formation processes. We can then expect that the properties of a galaxy’s host dark matter halo (e.g., mass) can play a pivotal role on how the underlying galaxy evolves over time. However, dark matter is (at least at the moment) not directly observable on an astrophysical scale with the technology and level of understanding we have today. Therefore, for us to infer information regarding host dark matter halo properties requires we use a proxy that traces the underlying dark matter distribution in the Universe.

One popular approach is using galaxy - galaxy clustering with the main idea being that galaxies reside in DMHs and, therefore, tracing how clustered galaxies are would then give us an idea of how dark matter is also distributed. This is done by use of angular (and spatial) correlation functions which is a statistical tool defined as: \[\begin{align} P(\theta) & = n (1+w(\theta)) \end{align}\]

and describes the probability of finding a galaxy within some angular separation, \(\theta\), and a mean number density, \(n\), and an angular correlation function, \(w(\theta)\), that describes the deviation from a randomly distribution of galaxies (e.g., \(w(\theta) == 0\)). This can be converted into a spatial correlation function, \(\xi(r)\), using the Limber equation (e.g., CITE SIMON2007) defined as \((r / r_0)^{-\gamma}\) where \(r\) is the spatial separation between two galaxies, \(r_0\) defines the clustering length, and \(\gamma\) is the slope of the spatial correlation function. Coupling this with a dark matter halo occupation model, one can then infer the typical halo mass of galaxies for a full sample or in bins of physical properties.

Figure 1: The clustering length, \(r_0\), and its evolution (Khostovan et al. 2019) for different sample selections ranging from emission lines to continuum selection (e.g., UV, BzKs) and far-IR selection (e.g., SMGs and DOGs). There is no clear trend between selection types and samples of the same selection also do not agree with each other. This is due to different samples having different limiting ranges of physical properties that can bias the resulting \(r_0\) for the full sample when compared to other samples. This is clear for Lyα emitters observed with intermediate bands which are all above deeper and lower EW narrowband-selected Lyα emitters.

Figure 1: The clustering length, \(r_0\), and its evolution (Khostovan et al. 2019) for different sample selections ranging from emission lines to continuum selection (e.g., UV, BzKs) and far-IR selection (e.g., SMGs and DOGs). There is no clear trend between selection types and samples of the same selection also do not agree with each other. This is due to different samples having different limiting ranges of physical properties that can bias the resulting \(r_0\) for the full sample when compared to other samples. This is clear for Lyα emitters observed with intermediate bands which are all above deeper and lower EW narrowband-selected Lyα emitters.

I led an investigation of how galaxies and their host halos co-evolve in two papers (Paper I and Paper II where I measured the angular correlation functions for samples of [OIII] (\(0.8 < z < 3.2\)) and [OII] (\(1.5 < z < 4.7\)) emitters from HiZELS in Paper I and Lyα (\(2.8 < z < 5.7\)) emitters from SC4K in Paper II. We found disagreements in the clustering lengths when comparing sample-to-sample which is caused by selection biases.

Figure 2: The host dark matter halo mass as a function of line luminosity normalized by \(L^\star(z)\) from Khostovan et al. (2018).

We then investigated the clustering length and host dark matter halo masses as a function of line luminosity normalized by the typical luminosity (\(L^\star\) from the luminosity function). I found strong, redshift-independent correlations for all emission line selections up to \(z \sim 6\) where faint (bright) emitters typically reside in low-mass (high-mass) halos. However, the correlations becomes shallower at \(L > L^\star\) independent of line selection. This is consistent with a transitional halo mass predicted in simulations where cold gas accreting into galaxies is shock heated above a halo mass limit (few \(\sim 10^{12}\) M\(_\odot\) to \(10^13\) M\(_\odot\)) resulting in decreasing numbers of star-forming galaxies with increasing DMH mass (‘halo quenching’). Observationally, this is seen as a shallower correlation between halo mass and line luminosity above a halo mass limit. The main conclusion from both works is that DMH properties play an important role on how SF activity occurs in galaxies. Furthermore, bright emitters (\(L > L^\star\)) may be important probes of investigating galaxies experiencing halo quenching.